Title (as given to the record by the creator): The Political History of Fat Liberation: An Interview

Date(s) of creation: February, 1981

Creator / author / publisher: Judith Stein, ReaRae Sears, Pam Mitchell, Robin Newmark, The Second Wave: A Magazine of The New Feminism

Physical description: Black and white scanned photocopy from a magazine, 6 pages

Reference #: SecondWave-FatLib-1981

Source: Judith Stein

Links: [ PDF ] [ The Second Wave: A Magazine of The New Feminism ]

The Political History of Fat Liberation: An Interview

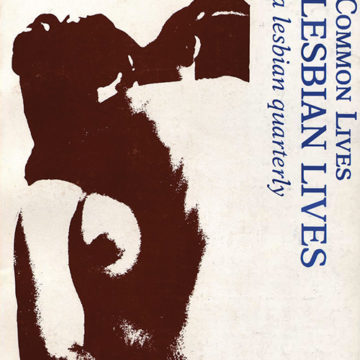

[image description: Black and white photocopy of a photo of two smiling, white, fat dykes.] Photograph by Susan D. Fleischmann

The Political History of Fat Liberation: An Interview

interview by Pam Mitchell and Robin Newmark, edited by Jennifer Purnell

Editors’ note: On February 1, 1981 two members of The Second Wave collective interviewed ReaRae Sears and Judith Stein, two Boston feminists active in the Fat Liberation movement. The following is an edited excerpt from this interview.

SW: Can you tell us a little about the early history of the Fat Liberation movement?

JUDITH: A lot of work was being done in Los Angeles in the early seventies. In L.A., radical therapy was a big force in the feminist community. It wasn’t traditional feminist therapy in any way, and it was very much about political issues and also dealing with therapy in a political way. So out of a radical therapy group in L.A. this group called the Fat Women’s Problem Solving Group was started. At the same time there was an organization called the National Association to Aid Fat Americans (NAAFA) which still exists. I think it’s fair to characterize NAAFA as a liberal organization primarily concerned with civil rights and social access for fat people, because a lot of fat people don’t have good access to social situations – if they go out dancing they’ll be laughed off the dance floor. The organization was overwhelmingly heterosexual. Some of the women in the Fat Women’s Problem-Solving Group were also involved with NAAFA and as they began working with feminists in a feminist setting on issues around fat, they became increasingly dissatisfied with NAAFA, which is a mixed organization in every possible way. So these women formed another organization called the Fat Underground. It was one of the first radical Fat Liberation groups. They wrote some statements and distributed them and did some public actions. For example, when Mama Cass (the singer from the Mamas and the Papas) died it was treated very badly in the media. The Fat Underground staged a public protest because it was treated as a big joke that this big fat woman died. Eventually the Fat Women’s Problem Solving Group came to an end – most of the women had become involved in the Fat Underground. Over the course of the next couple of years the Fat Underground became inactive too. I’m not sure whether they’re active now.

Some of the women in that group continued to do Fat Liberation work. One of them was Judy Freespirit. She worked with a group of women called Fat Chance, which was a fat women’s dance and acrobatics troupe.

SW: What happened to that group?

JUDITH: They’re not performing together. They were a group of fat women who wanted to dance and who didn’t feel safe exploring dancing and acrobatics with women other than fat women. So they came together and they did these performances which were really powerful. As they began to talk about continuing to stay together, other issues came up which they never had to deal with before and which they couldn’t deal with in a way that would allow them to all stay together. They are still in touch but they aren’t dancing together.

SW: What else was going on in the early seventies?

JUDITH: Vivian Mayer (writing as Aldebaran) on the East Coast did a lot of the earlier writings of Fat Liberation and founded Fat Liberator Publications. But she was very isolated – there were little isolated pockets of fat women doing things. The response to Fat Liberation by feminists was very bad. Aldebaran sent an article to a very respectable lesbian publication which doesn’t exist any more and got it back with “I don’t believe this, this is bullshit” scrawled all over it – this was their reaction. Another publication lost her manuscript three times, and after a certain point of losing manuscripts it’s more than carelessness. I think this reaction had a lot to do with the relative isolation of fat activists, and I also think the era was very bad. People saw Fat Liberation as someone’s personal vendetta, or as someone’s personal issue as a fat woman. Thin women and other fat feminists were unwilling to see that this was yet another form of social control that was really keeping us all down.

SW: Is this reaction changing?

JUDITH: Within the lesbian community and some of the feminist community that’s starting to change. Mainstream America hasn’t even heard of us yet. Even within the feminist press there are still a lot of things; like you don’t see diet articles within the lesbian and feminist press, but you see a lot of references that are oppressive to fat people. You still see people called fat capitalists or fat pigs. You’ll still see “letting go of fat” workshops led by feminist therapists, that are really based on the assumption that everyone really wants to be thin, and if they don’t they must really need therapy. I used to go to lesbian raps when I was first coming out and I heard more times than I can count about how .. , used to be really fat and I was really shy and uncomfortable in social situations. Then I came out and became a lesbian and the pounds just dropped off. The statement behind that is “I used to be untogether and fat and now I’m together and thin.”

REARAE: People are so unaware of fat oppression that they’ll say the most outrageous things that they would never think of saying to someone within another oppressed group to a fat person and have no concept that they are being outrageous and really oppressive. An example of this in the feminist press happened to a friend of ours who’s a Fat Liberation activist in the South. There’s this therapy collective in her community which everyone loves because they’re these groovy women who do lesbian therapy. And thev ROI this group together called “Letting Go of Fat.” This woman, who was an editor of the lesbian paper, didn’t want the ad for the group to go in the paper. The other women on the paper said that was censorship, that she couldn’t tell other women what to do. She said. “Well. I’m sure that if we got something really homophobic ot really racist as Jn aJvertisement you wouldn’t allow it to go in.” And they Jidn’t see the connection at all. They knew that she’s a fat activist. She wrote articles for the paper on Fat Liberation. she’s done all these things and they still had the audacity to ask her to retype the stencil for this ad. They said there’s a lot of fat women who want to be thin. They didn’t make the connection that when DOB was starting or some of the really early stuff, that there were a lot of gay people who wanted to be straight. There still are, because it’s easier when you’re straight, easier when you’re thin, easier when you’re white. But the myth is that you can take care of being fat. The truth is that over a five-year period 94 to 99 percent of all weight loss attempts fail. Even within the lesbian community, within the feminist community, people will say, “Well, it’s not really fair that fat people get jokes made about them, but you really could do something about it.” There is that myth of control of your body size. And women who are not fat are encouraged to feel that way because it keeps a lot of women really preoccupied with what they are eating.

JUDITH: In order to understand Fat Liberation you have to understand fat oppression. Fat oppression doesn’t just affect fat people or fat women. It really works to keep everyone in line. It’s a whole system of social control that keeps thin women absolutely terrified of being fat, or thinking they are fat, and a whole lot of energy goes into dealing with fat. It keeps women who are medium-sized absolutely panic stricken because they are right on the border. Those of us who are fat are over that border into some state of evil, basically, very much outside of what is permissible within white American culture. If you are fat, then what you are supposed to do is strive desperately to get not-fat. if you’re medium you’ve really got to toe the line because you’re almost there. And if you are thin you can either feel superior or you can worry about every two bites you put in your mouth. Because the mythology about fat extends to the point where it’s very difficult to define what being fat is. As odd as it sounds, that’s a chronic problem in Fat Liberation work, saying, well, who is fat? I’ve met women who are literally 90 pounds who are convinced that they are fat. They really self-identify that way. Or women who the insurance charts say should be 120 pounds, and they are 135, and they walk around saying they gained five pounds, that they look so ugly. They say this to me.

SW: How do you define fat?

REARAE: Well, it’s really hard to define. One of the reasons that it is hard to define is that the insurance tables, upon which obesity science is based, were drawn from a very select thin group of people in 1956. They are really drawn from a totally unrepresentative population, from white middle and upper class educated people who bought life insurance in the fifties.

Mostly in the work I’ve done we’ve used a set of questions as guidelines. One is, where do you buy your clothes? If you buy women’s clothes, do you have to go to a special section of the store? Do you have to go to a special store? Are you perceived as fat relative to the general population on the street or next to people perceived as normal sized people? Is your mobility restricted because of your size? Do you have trouble getting through turnstiles on subways?

JUDITH: Because there is such an anti-fat ideology, particularly in white culture in this country and this century (it hasn’t always been the case), women who weigh over whatever they perceive that they ought to weigh define themselves as fat. Or women who experience any kind of body hatred – which is just about all of us – often perceive that as being related to being fat. I was once at a fat women’s liberation group and encountered a woman who was definitely not fat – very stocky, fairly androgynous looking. She got a lot of shit for the way she looked. She perceived that as fat hatred – that’s how she heard it – when in fact she just didn’t have what is considered an appropriate female body because she was big, and stocky, and tough-looking. So a lot of body hatred is identified as fat stuff. Women, especially, have a real range of body shapes. I think that it would be really difficult to grow up female in this culture and not grow up with a load of body hatred. So I wouldn’t ever want to say to a woman, “You can’t possibly know what it’s like to hate your body because you’re not this or you are this.” It’s not a useful approach, it’s not functional, it’s just not accurate. But women of different sizes have different experiences. At 250 pounds I get by a lot easier than someone who is 450 pounds. Both in terms of physical access and in how I am perceived in the world. I don’t get assaulted verbally every time I walk down the street. I do get more than some women who are smaller than me.

It’s a very difficult thing, but in no way am I or is Fat Liberation trying to say, “well, we are the only ones who experience body hatred. We don’t have a corner on the market at all. It can be very ethnically or racially related. I know a lot of other Jewish women who have big breasts

and big hips because that’s the way their genes go, the way their bodies go. They’re never going to be fat, and yet they are going to experience a lot of problems in their lives because in this culture they have the “wrong shape.”

I think part of the problem is that there’s incredible denial among fat women. We are really just starting to acknowledge what size our bodies are. I’ve been doing a lot of Fat Liberation work for a number of years now, and I have a really poor concept of what size I really am. Every time I meet someone who is about five feet, six inches tall, and weighs about 250 pounds, I ask ReaRae to tell me how my body is like hers and how it is different. Because I really have no models. It’s very hard to figure even what size someone is. And that’s a very basic level of denial, because it is really a question of how much space your body takes up. It’s a really disempowering kind of experience to have no idea what you look like. I was taught in a whole lot of ways not to look in mirrors, to wear clothes that would draw no attention to me, to sit… a lot of this will be very familiar because it is standard female socialization, but it’s really magnified if you’re fat… to sit quietly, to sit in corners, to be polite, to be grateful that I was in a social situation at all, wherever I was. There were a lot of things that encouraged me to be a little tiny person even though I’ve never had a little tiny body, and it was a very schizophrenic kind of approach to the world – trying to make myself look physically as small as possible when in reality there’s this big body and I occupy It.

REARAE: You know how it was to wear a tight girdle. These are designed to make women three or four sizes smaller. That’s one level of fat oppression. But a harder level of fat oppression is that fat is one of the few things you can be and people will still make jokes about you. And you really are supposed to tolerate it, if not enjoy it. A lot of people will internalize fat oppression so much that we laugh right along. If you just look through the Boston Globe comic strips I would wager that you can’t get through a single day without an anti-fat joke in at least one of the comics.

JUDITH: Or a fat character being the butt of a lot of jokes. In BC, which is a caveman comic, the fat woman is always chasing the man and he’s never interested, and she always looks like an idiot. She’s also a “women’s libber” and we all know that the reason she’s a “women’s libber” is because she’s fat. Ha, ha, ha.

One form of fat oppression is verbal harassment on the street. People feel absolutely free to say anything to you if you’re fat – about your diet, your appearance, about your clothes. We just heard tonight about this woman who was approached by two young women on the street. They asked her, “Do you know where Weight Watchers is?” She thought they were asking for directions and she said, “No, I don’t.” And they said, “Well, you should.” I know someone else who went into Jordan Marsh [a department store] and said, “Where are your large size pants?” Instead of answering her question the sales clerk said, “Why don’t you just eat a little bit less?” That’s common. But the other extreme of fat oppression is not being able to get certain kinds of jobs, because you don’t suit the company image or policy. And there’s no legal recourse. If you don’t fit the company weight guidelines you have no recourse at all. If you are fat, and denied a job, or fired, and that is the sole basis or you are told that it is, there is nothing that you can do.

REARAE: Women have gone to lawyers and the lawyers have said, “You should lose some weight.”

JUDITH: One of the early fat activists was told to go to Weight Watchers, and that would solve her problem. Fat women are told that they are too high a risk for surgery because they are such a high risk in recovery. On the other hand, we are offered any number of kinds of surgery that theoretically produce weight loss. You can get your jaws wired shut so that you can only take in liquid foods. This is despite the fact that over 70 deaths have been attributed to liquid protein deaths by starvation. There’s probably been more. There is this other procedure called an intestinal bypass, where they cut out about three-quarters and more of your intestines so that food just goes right through. This causes diarrhea for the rest of your life, and you lose all kinds of minerals.

REARAE: Your whole body balance gets really screwed up. Six out of 100 people die from the surgery alone. That’s a very high number. There’s one doctor I know about who in one year did 900 gastric staplings as an experimental procedure. In gastric stapling, they staple your stomach to make it smaller. His fee alone, per patient, was $2700. Originally he was doing intestinal bypasses, but he said that was too dangerous. So to fat people who are supposedly such high risks for surgery anyway, who have already had major abdominal surgery – the bypass – he performed a second operation, reconnecting the intestine.After they healed, he did a third major operation – stapling their stomachs. Half of the people he operated on had to have it redone; the hole that was left was either too small. or it was blocked up, or it was too large. In other words, these people had three or four major abdominal surgeries, and they are supposed to be high-risk surgery patients to begin with. The stapling stuff is horrible. People can eat about ten ounces of food at a time – about a cup and a quarter. lf you eat more than that you can rupture your stomach, and then you have an abdominal infection and everything. And people are not losing that much weight with the stapling or the bypass. People my size are losing maybe 50 to 80 pounds. And doctors tell them beforehand that they are going to lose all 200 pounds or whatever they have to lose.

One of the things that lately has become a beef of mine is that – how many deaths have there been from toxic shock, under a hundred? Some of the feminist health centers and other places are really up in arms about it. It’s this big horrible thing, and they are trying to kill women, and why didn’t they do research on it before, and all this stuff. There’s 27,000 diet and weight loss related deaths per year, and the majority of them are women. And who’s hollering? No one is hollering. Because we are told that fat is bad, and it is unhealthy for you, and dying for one of these “cures” is better than being fat. Fat oppression is based on certain assumptions, one of which is that you can do something about being fat, that it requires a change in eating habits, that fat people eat the wrong foods, the wrong kinds of foods at the wrong times for the wrong reasons.

JUDITH: Over 100 studies have tried to prove that fat people eat differently from thin people, and they never end up proving that. But that’s not the kind of information that gets out. It’s certainly not what the average woman on the street thinks. She’s convinced that fat people must eat too much, or eat a lot of sugar, or never exercise, when exercising is difficult because you can’t get exercise clothing in your size and you can’t use facilities because of your size. It’s a really vicious cycle.

SW: What forms does fat oppression take specifically in the feminist and lesbian communities?

JUDITH: With the push to be strong in the feminist community – and I have no quarrel with that – there are these assumptions, one of which is that you must be thin. You can be muscular, you can be jocky. Within the lesbian community there is a fairly wide range of acceptable body types. But they definitely stop short at the sort of butchy, androgynous jock body, and if you are bigger than that you are over the limit. If you are fat then you are clearly not being a good amazon. So the cultural myths within the feminist community, and within the lesbian community, have only shifted, they are not really that much different.

REARAE: Within the feminist community, dieting is sort of disguised under health food, and a lot of women are on health food diets. A lot of what they’re hoping is that they’ll lose weight or that they won’t gain weight. They would never go to Weight Watchers or to TOPS or to Diet Workshop, but they will go on some kind of extreme health food diet.

JUDITH: I think that the problem within the feminist community is that a lot of anti-fat feelings get either boxed in under this thing, “well, you can do something about it” or “well, alright, maybe you can’t deal with it.” Then they get into health issues and say “it’s really not so healthy to be fat.” Which is true in terms of stress related problems, because it’s a high stress existence to live in a culture that tells you you’re worthless and that it’s your own fault. If you’re fat then this culture considers that it’s your fault because you’re not doing something to cure it, or fix it, to lose weight. So it becomes a moral issue. You have bad morals or poor character, no backbone or willpower – all of these things. So it remains an individual’s problem, if an individual is fat.

REARAE: And because this culture is so down on fat people, fat people have an incredibly high incidence of stress related diseases that also show up in other oppressed groups – high blood pressure, diabetes, those kinds of things. With fat people they will say it’s because you’re fat.

JUDITH: Most feminists and lesbians are too cool to say being fat is icky, even if that is what they really think.

REARAE: They’ll just say, “oh, I’m just not attracted to fat people,” or “I know that it’s a real problem for your health.” Because most feminists and lesbians have internalized the fact that it’s not cool to tell someone they’re ugly.

JUDITH: It’s hard not to pick up that message, though. That fat people are ludicrous, terribly unattractive, and grotesque. I think in the feminist community there is this ethic about who is a high status lover if you’re a lesbian, and what the high status activities are to do. A lot of that is sports and those physical strengthening activities which are very difficult to do if you are fat. Especially if you have 20-odd or 30-odd or 40-odd years of being discouraged from doing physical activities. It’s very hard to go out on the softball field and pick up a bat and do something right after all those years of not having any access to it.

A lot of women in the feminist community don’t see that Fat Liberation has anything to do with themselves, and that’s a real limit because in the same way that dealing with issues around class or race or heterosexual privilege has to do with all of us, Fat Liberation has to do with all of us. Because it keeps all of us boxed in some place or another along the spectrum of what’s okay and what’s not okay in white American culture. Women are not the ones who set up those standards, but sometimes we do a really good job of keeping them in place. That’s where horizontal hostility comes in – thin women can feel superior to fat women, fat women can feel superior to women who are fatter than they are. All of us are really worried about what our bodies are like and what we eat and how what we eat will affect our bodies. It keeps us really tied up when we could be taking on the people that are putting down the standards in the first place.

REARAE: I want to talk about what activists around the country are doing now. I like what we are doing. After getting together at the Michigan Women’s Music Festival in 1979, radical women went back to their communities and started doing things, started support groups and started finding other fat activists or fat women in the community that we can work with. So now here in Boston there’s a loose coalition of about half a dozen women. We put out a newsletter for Fat Activists and do Fat Liberation groups and workshops. We’re also into doing radio shows, panels, forms and such.

SW: Do any of you work with other feminist groups on fat issues?

REARAE: One of the women is really active in Take Back the Night. She has been talking to the group about including weight loss surgery as part of violence against women, and they’ve been responsive. I think the Boston women are doing a lot of outreach outside the fat community – into the gay and lesbian press, the feminist press, a lot of public stuff.

There’s probably about half a dozen women in Minnesota doing work with north midwestern women. They get together every six weeks or so for a weekend. They hang out or go camping together, they do workshops and go out to eat and go dancing. They’re doing a lot of work within their own community, within the fat lesbian community, which is really exciting because we hear from them that it is really strengthening a lot of women. They also have more larger women than we do here, a number of women who are 300 and 400 pounds. Fat women who are my size aren’t seen in public much. I often go to concerts where I am the largest one. the only one of my size. From the work I’ve done I know that there are a lot of women bigger than me who don’t go out to events. In some places. if you’re much bigger than me, you can’t fit into the chairs. So women who are bigger than me just know that they can’t go to these places and sit anywhere. I come from what I call a “rights-bearing” attitude – I have a right to be at those places and women need to accommodate me like they accommodate other disabled women. But not everyone is coming from the same position. So for the north midwest area to have four women over 400 pounds who are active – that’s pretty incredible.

JUDITH: I think that the Fat Liberation Movement’s development is parallel to the feminist movement, which is no accident because the leaders have also been activists in the feminist community. The first step is networking and mutual support, and I feel like that’s a lot of what’s gone on for a lot of us over the last few years. I think that networking and support go on in a lot of forms in the same way that early feminists or early lesbians got together and just said, “hey, we’re really alright,” “we’re not wacko,” “we’re not sick.” There’s a whole lot of that level of validation that has to go on because of all the invalidation that comes down constantly from the culture as a whole. In some communities women have had enough support that we’re feeling more able to take on the world at large (laughter).

AFTERWARD

by ReaRae Sears and Judith Stein

The Fat Liberation Movement is now a loose coalition of groups and individuals who are working to end harassment, ridicule, and discrimination against fat people. Fat Liberation sees that oppression as part of a system that harasses and oppresses women, poor people, people of color, Lesbians and gays, and disabled people. The oppression of fat people, for being fat, is based on certain myths which are almost universally held to be true, and which are supported by an enormous industry which includes doctors, diet companies, and drug companies among others. Although the preceding interview is more a political history of the Fat Liberation movement than an introduction to Fat Liberation theory, certain facts are essential to understand Fat Liberation’s position. All of them contradict everything we are taught about food, fat, dieting, and health. For more information, contact Fat Liberator Publications, P.O. Box 5227, Coralville, Iowa 52241.

Here are the facts underlying Fat Liberation’s political positions:

- Fat people are not fat because we eat more, more often, or differently than thin people. Of over 100 studies attempting to prove that eating wrong (in some fashion) causes people to be fat, every one has failed. Fat people’s eating patterns cover the same wide range as thin people’s.

- Weight loss diets, of all types, have a 94-99 percent failure rate over five years. This is true for both “sensible” and quack diets. Not only do weight loss attempts fail, they have been proven to be physically harmful. causing increased high blood pressure and risk of heart attacks, among other things. In addition, of the 94-99 people who gain back the weight lost, 90 percent will gain back more weight due to metabolic changes produced by the dieting process itself. Diet failures and the resulting weight gain have nothing to do with willpower, good character, etc.

- The pain fat people experience in the living of our daily lives is not our individual problem, but part of a medical, social, and legal system which says that fat people are not as good as thin people. Hatred of fat and fat people is as widespread and deep as sexism, racism, etc. Because being fat is held to be an individual’s “fault,” most people feel that whatever bad treatment fat people get is really just what we “deserve.” Therefore, there is enormous support for fat jokes, street harassment, pressure from family, doctors, etc. against fat people. The effects of fat oppression, not any inherent misery of being fat, is what creates high-stress painful lives for fat people, and especially for fat women.