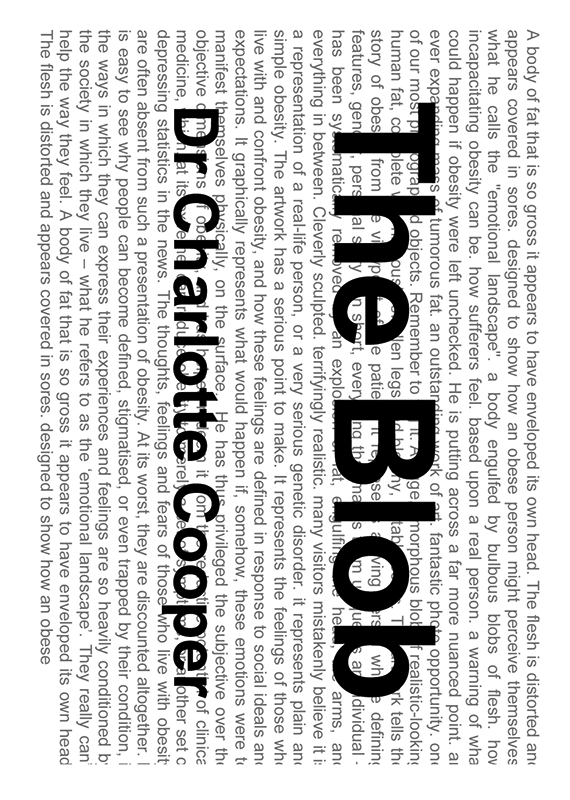

Title (as given to the record by the creator): The Blob

Date(s) of creation: 2016

Creator / author / publisher: Charlotte Cooper

Location: London, UK

Physical description: Half size zine, 2 sheets folded in half to make 8 pages.

Reference #: CharlotteCooper-TheBlob

Source: Charlotte Cooper

Links: [ PDF ] [ Website ]

The Blob

This zine accompanied a performance by Charlotte Cooper at the Wellcome Collection museum in London in 2016.

Entering the hate zone

When I was a girl in the 1980s, I would often visit the Wellcome Collection, which then was tucked away on a quiet floor of the Science Museum. Until now I never thought that these visits might have prompted my interest in medicalisation. I just liked looking at gruesome medical implements and thinking about bodies. Well, I still do. Perhaps without those visits I would have found it harder to understand disability activists’ critiques of medicalisation, or apply the Social Model of Disability to my own fat activism. Who knows?

Obesity is a section of the permanent display called Medicine Now at the Wellcome. It opened in 2007, during the first flush of obesity epidemic rhetoric. It is presided over by a large sculpture called ‘I Can Not Help the Way I Feel’ also referred to with the grammatically tidier ‘I can’t help the way I feel’. Here a universalised fat body is rendered as a diseased, pitiful, sexless, grotesque blob on legs. I think the title is stupid and affected so I call it The Blob. This blob has no head or identity, it is an unending eruption of abjection.

In front of The Blob is a cabinet with drawers full to bursting with weight loss technology. To the left a towering bookcase of diet books, mostly pink so that women know they are directed at them. To the right some exercise equipment. There are some audio recordings of medics and anti-obesity people. One recording by a fat woman that I have never been able to listen to in the context of the rest of the objects in that space, her presence is too sad for me to cope with. She is apparently a fat activist, but I have never heard of her. Where did this token come from? Who is this box ticker?

Funnily enough, Obesity in Medicine Now is a perfect rendition of obesity discourse: bizarre and absurd medical technology; messianic, hubristic, pleased-with-themselves medics and anti-obesity proponents; unimaginable profit and greed built on (mostly) women’s self-loathing; a discourse that expertly wields hate; a discourse that marginalises and patronises the very people it is supposed to be about; a mind blowing lack of critical self-reflection or humanity.

I am one of the most prominent and accomplished fat scholars and activists in the land, maybe the world, and I can’t handle this space. I saw it once and never returned. It’s one of the things that makes me feel that, for fat people, the Wellcome is really – wait for it – unwelcoming. Whenever I’m in the building, I know where I am in relation to the display, The Blob in particular. It’s like we’re attached with string. One of my survival tactics is to try and disregard the hatred of fat people like me, and try and live my life on my own terms. But that strategy does not work here, the hate is there, endorsed and celebrated at the highest level, transmitted as though it were truth through the profound arrogance of medical science. Sometimes I’ve been to the building and have had to go past it so I avert my eyes, but I know it’s there. I feel on edge, sick, tense whenever I think about it. Even writing this has given me backache.

Transformative dancing

Public sculpture is a reflection of who has power, turf, permission, access, funds. But it is possible to alter an oppressive sculpture. You can pull down a monument to Saddam Hussein or Enver Hoxha. You can campaign to get rid of Cecil Rhodes. You can build a place like Memento Park in Budapest, which is a memorial and a critique of a dictatorship. You can give Winston Churchill a mohican made of grass, or Donald Trump a big belly and a tiny penis, and then you can photoshop an anti-body-shaming sandwich-board over the top and turn it into a meme.

You can dance.

I have a dance called ‘But is it healthy?’ At Body Language, I will be using the dance to relate and speak to Obesity and The Blob in particular. I will be dancing with my partner Kay Hyatt, who also developed the dance. The soundtrack will be based on archival recordings by fat feminist activists. This will have been the first time I have used this dance as an intervention in a public space but I’m hoping to do it again elsewhere.

But is it healthy? is the question that people always ask whenever I talk about fat stuff in public. They are looking for a yes or no answer, and they expect someone to have that answer, which they believe is based in expert scientific research. But it is an impossible question to answer, not least because fat people are a diverse group, health is constructed in myriad ways, and expert science is not incontrovertible. Over the years I have become sick of this question. I can’t control who asks it but I can control how I answer. So now I have a dance as an answer, this feels more satisfying.

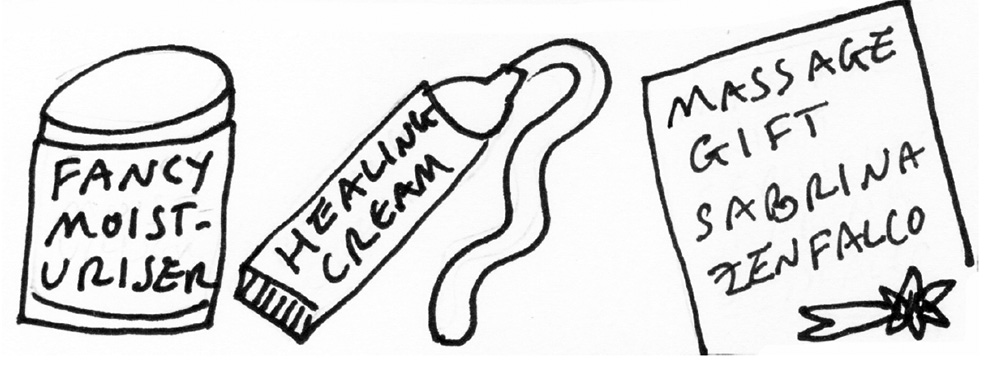

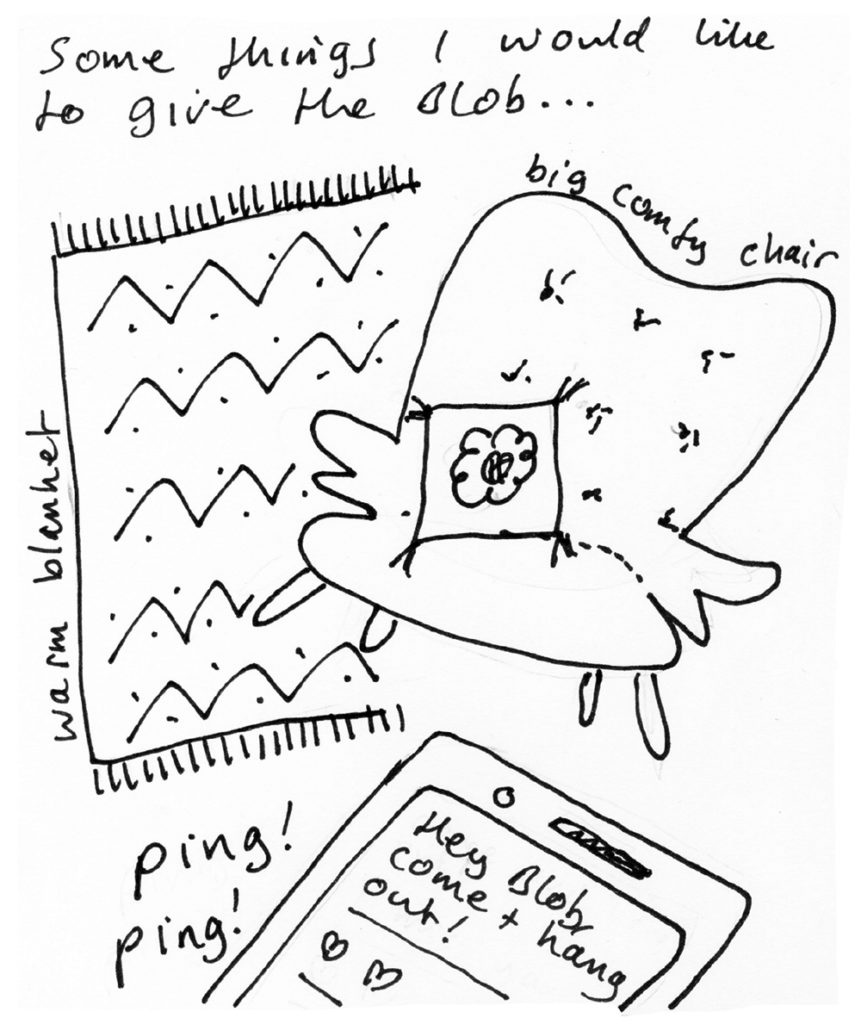

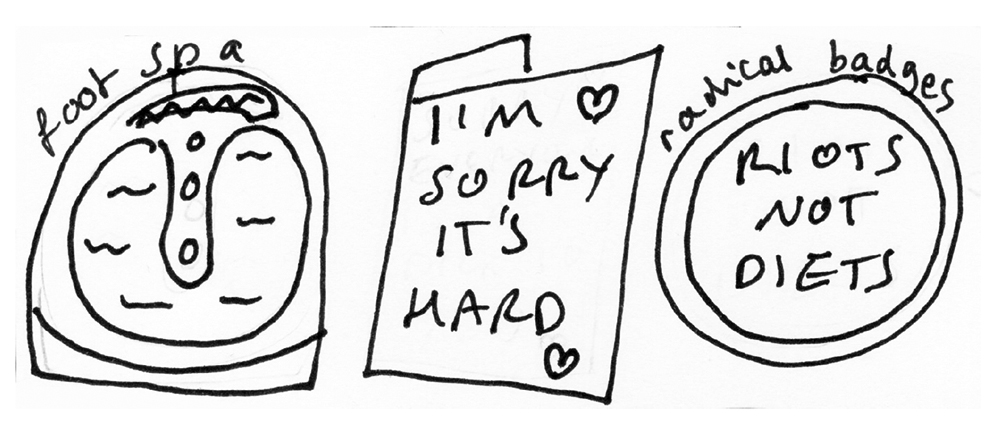

Dancing ‘But is it healthy?’ in the Obesity exhibit is an act of resistance, of disrespect, a creative critique. I am hoping it will be a dance that exorcises fatphobia (cf Jamila Johnson-Small), that reclaims a space and creates another way of seeing. I would like to reinstate fat personhood, humanity, agency, culture, community, history in a space that has erased it. When we did a site visit in September 2016, Kay said that she felt The Blob needed a friend and that we could be its companions. Fine by me. It’s also a dance to soothe my pain.

I have another secret hope for the dance, and that is that it can be something that anyone can do in any space where fatphobia is present. For example, it could be a dance that anybody did whenever they saw The Blob.

Who gets to call it?

I tried to keep an open mind. Fat grotesque is powerful because it is a reminder that good citizenship can also feel suffocating, it makes space for the Other, the unallowable. It’s another route to freedom.

But then I saw that the artist isn’t fat. Maybe he has body dysmorphia but that doesn’t mean he knows what it is like to be as fat as his figures, or to know the “emotional landscape” of fat people, whatever that means. I read his psychobabble rationale for The Blob, utter wank. I saw that he’d made many other blobs. I realised We Can Not Be Friends.

All this made me think of Jenny Saville, thin, power-suited in the picture, Saatchi-fied, and her paintings of fat women’s and trans bodies, which are not hers but to which she has added her own face.

It made me think of Martin Rowson, cartoonist with The Observer, who uses bloated, leaking fat human and animal bodies to represent political greed and corruption.

It made me think of a blog post of mine, one that gets a lot of traffic because it used to have the word ‘fetish’ in the title until I changed it (people who search online for fat people are often looking for pictures to jerk off over in secret). This post is a critique of abstract sculpture that fetishes fat people as cuddly, soothing, maternal. Still dehumanised but a different kind of grotesque.

And it made me think of Fernando Botero’s ‘Broadgate Venus’ in Exchange Square. It’s really saying something that the dirty, greedy, banking heart of City of London can make a better stab of commissioning fat sculpture than the enlightened museum.

Abstracting fat bodies is a thin artist’s version of a headless fatty, they can make universal claims based on their own fatphobia without having to be accountable to the fat people they are exploiting.

Who gets to call and use fat grotesque? Does its use always have to be part of a liberation project? How might normatively-sized artists depict fat people ethically? What do they need to understand about the long-standing oppressive practice of treating fat people as fodder, material, research subjects in spaces where those very people rarely have a voice, power, presence of their own?

Wake up! We fat people are capable of telling our own stories. Many of us are artists and scholars and activists with so much to say. World-changing things.

What about including Venuses, megalithic sculptures of fat women from Malta, from Turkey in the exhibit? These ancient representations show that fat people are part of humanity and not a recent crisis of too much bad food. Rachel Herrick’s Museum for Obeast Conservation (obeasts.org), is a project creatively lampooning the use of fat

people as curatorial material. It would be perfect for this space, as would Ladies Sasqatch by Allyson Mitchell a series of witchy, crafty, monstrous, queer fat beasts.

There are masses of naïve fat-positive knick-knacks made by fat activists and sold on Etsy, they’d be great too. There’s work from Substantia Jones’ Adipositivity Project, pieces by Scottee, Selina Thompson, Kayleigh O’Keefe and so many more. This would transform the display, but maybe the Wellcome doesn’t want it to be transformed, maybe the display supports something fundamental to the institution, medicalised fatphobia, and that cannot be changed.

Biting the hand

The Blob is not a cheap piece of work. Artists’ studios, microcrystalline wax, polyester resin, expanding foam, polystyrene, oil paint and steel don’t pay for themselves. The Wellcome has needed to extract value from their investment in this sculpture. They do this through PR. As a result, the image pops up all over the place because the Wellcome is an influential institution. It’s hard to make a living as an artist if you don’t have a private income, and I imagine it’s been a really good career move for the artist.

Text on the museum’s blog and website, always breathless and positive, explains how The Blob reveals so much about how fat people feel, that it is a highly well-informed piece of work. It’s like they’re having to re-convince themselves that they’ve done the right thing in buying and supporting this piece. It is considered progressive to use the arts to explore medical science, that is what the curators have tried to do here, except they have made the mistake of using fatphobic art to explore what it is to be fat.

This has resulted in more fatphobia in the Wellcome, through the language they use to talk about the sculpture and the exhibit, the clichés they invoke (a passage about hauling in the sculpture through the window sounds a lot like the shockumentary trope of fat people being hauled in and out of buildings to be hospitalised). The institution may not yet be able to acknowledge that they are part of the problem it is undeniable that if anything reproduces fat hatred and stigma, it is this display, which has been endorsed everywhere from the BBC to the New York Times and beyond.

The fatphobia engendered by the exhibit is further transmitted through the visitors who are then re-appropriated for the institution! A blog post and special Tumblr celebrates the number of visitors who take amusing photographs of The Blob. Bright, shiny, young, thin, mostly white people. They pull unnerved faces, look for the figure’s genitals, pretend to cup its arse, pretend to kiss it, point at it, do chin-stroking actions (obesity is such a conundrum!), add their own shitty captions (“Over McDonalds ed”). Perhaps these are the same people who pose for selfies on Holocaust memorials, or by the vulva of Kara Walker’s ‘The Sugar Sphinx,’ a sculpture about slavery.

There are no images of fat people interacting with The Blob. Although readers are repeatedly told that this sculpture represents how fat people feel, there is no material from fat people to support this view.

The Wellcome’s attempts to engage with fat activism, or even critical views of obesity discourse, of which there are many, are dismal. This is a tactic I have seen employed elsewhere by similar upholders of anti-obesity rhetoric. They either pretend critical views don’t exist, minimise the extent of these criticisms, cite some isolated and underwhelming example of activism to support their position, or ally themselves with the most conservative proponents, usually The Rudd Centre at Yale, which adopts the paradoxical position of being anti-stigma but pro-weight loss. They use weird language, like ‘Fatism,’ which few fat activists use, and which reveals the extent of their cluelessness and alienation from the movement. Ironically, in one of its posts, the Wellcome blog refers to a concept I coined, but can’t quite get it together to cite me.

In the UK it remains rare for museums to acknowledge mistakes and become accountable. Stories of failure are pushed aside, they’re unpatriotic. The great museums and collections in this country often have direct relationships to colonialism, slavery, exploitation yet this knowledge is usually absent or denied. When I think of Wellcome I also think of GSK, who have major business holdings in anti-obesity products. It makes me think of Alli (“The healthy weight loss pill”) and of the euphemistic ‘anal leakage,’ one of that drug’s main effects. I can’t think of this place without also recognising that it has some kind of a relationship to the medical industrial-complex and the profitable project of getting rid of all the fat people.

Obesity in Medicine Now is one tiny example of how a museum has not been accountable to those it supposedly represents, and how it reproduces that group’s marginalisation through ‘kindly,’ pitying, abjecting oppression. Apart from one token inclusion, it speaks for fat people without really inviting us to the discussion and thus erases our radical contributions. It is no longer acceptable for institutions to represent fat people in this way, those days are over. It would be wonderful if this mistake could be acknowledged and the exhibit changed. I can imagine an incredible display about medicalisation that centred fat people’s voices. Imagine if there was a way of re positioning rather than censoring The Blob, so that, when people interacted with it, it destroyed rather than intensified their fatphobia. The opportunity to do something really powerful is there, but is the will?

I hope that my talk, my dance, my zine, my presence helps raise some questions about Obesity in Medicine Now. I have wanted to say this stuff since 2007 and only now have had the opportunity to do so. This is a risky thing. I am biting the hand that feeds and potentially alienating the kind and thoughtful people who have invited me in and supported my own work so generously. But who else is going to say something? The curators who commissioned Obesity in Medicine Now are unequipped to tell the stories that my comrades and I are able to tell. Fat people are not yet organised enough to target something like this collectively. So I’m saying something and I might not ever be invited back to say anything here ever again because what I am saying is not pretty. I do what I can do, but it can never be enough and it comes at a cost.

This is a zine that accompanies a talk and a dance I gave and performed at the Wellcome Collection on Friday 4 November 2016, part of the Friday Late Spectacular event called Body Language.

Contact me through my website if you have access needs for this zine. charlottecooper.net obesitytimebomb.blogspot.co.uk @thebeefer More of my zines: charlottecooper.bigcartel.com

Cooper, C. (1997) ‘Can a Fat Woman Call Herself Disabled?’, Disability & Society, 12(1), 31-41.

Cooper, C. (1998) Fat & Proud: The Politics of Size, London: The Women’s Press.

Cooper, C. (2007) ‘Headless Fatties’, [online], available: https://charlottecooper.net/publishing/digital/headless-fatties-01-07/ [accessed 16 September 2016].

Cooper, C. (2011) ‘A Queer and Trans Fat Activist Timeline – zine download’ [online], available: https://charlottecooper.net/b/oral-history/a-queer-and-trans-fat-activist timeline/ [accessed 16 September 2016].

Smith, C. (2012) ‘Under the radar: Fat activism and the London 2012 Olympics, an interview with Charlotte Cooper’, Games Monitor [online], available: https://www.gamesmonitor.org.uk/node/1647 [accessed 16 September 2016].

Cooper, C. (2013) ‘No more stitch-ups: media literacy for fat activists’, Obesity Timebomb [online], available: https://obesitytimebomb.blogspot.co.uk/2013/05/no more-stitch-ups-media-literacy-for.html [accessed 16 September 2016].

Gingras, J. and Cooper, C. (2013) ‘Down the Rabbit Hole: A Critique of the ® in HAES®’, Journal of Critical Dietetics, 1(3), 2-5.

Cooper, C. (2015) ‘I am a fat dancer, but I am not your inspiration porn ‘, Transformation [online], available: https://www.opendemocracy.net/transformation/charlotte-cooper/i-am-fat-dancer-but-i am-not-your-inspiration-porn [accessed 16 September 2016].

Cooper, C. (2016) Fat Activism: A Radical Social Movement, Bristol: HammerOn Press.

Evans, B. and Cooper, C. (2016) ‘Reframing Fatness: Critiquing ‘Obesity” in Whitehead, A. and Woods, A., eds., The Edinburgh Companion to the Critical Medical Humanities, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Front page text snaffled from Wellcome blog, BBC, Huntarian Museum.