Title (as given to the record by the creator): Life In The Fat Underground

Date(s) of creation: 1998

Creator / author / publisher: Radiance, Sara Golda Bracha Fishman

Physical description: PDF of a web page, 4 pages

Reference #: FU-Radiance-Fishman-1998

Source: Radiance

Links: [ PDF ] [ Radiance ]

Life In The Fat Underground

by Sara Golda Bracha Fishman

From Radiance Winter 1998

Southern Californians have a reputation for going to extremes, and for getting there before anyone else. It is no accident that Hollywood, purveyor to the world (via cinema) of the thesis that only the slender deserve respect, also produced its first radical antithesis: the Fat Underground.

The Fat Underground was active in Los Angeles throughout the decade of the 1970s. Feminist in perspective, it asserted that American culture fears fat because it fears powerful women, particularly their sensuality and their sexuality. The Fat Underground employed slashing rhetoric: Doctors are the enemy. Weight loss is genocide. Friends in the mainstream–sympathetic academics and others in the early fat rights movement–urged them to tone it down, but ultimately came to adopt much of the Fat Underground’s underlying logic as their own.

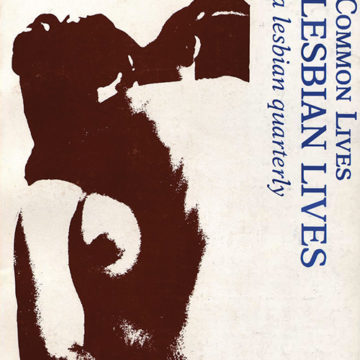

[image: Members of the Fat Underground reunited recently in Oakland, CA, at a Fat Feminest conference. Clockwise from upper left: Sara Fishman, Ariana Manow, Sheri Fram, Judy Freespirit, Gudrun Fonfa, Lynn McAfee]

Precursors

Radical means “root.” Radical liberation movements rarely try to change discriminatory laws. Rather, they demand change at the level of fundamental social values, which are seen as the root cause of all human laws. These values not only shape legislation, they also affect the way people view one another and treat one another in day-to-day interactions. These values influence the individual’s self-image, fostering self-hating attitudes and self-defeating behaviors in members of groups that society considers “inferior.” This insight was the driving force behind the Radical Therapy movement, a major precursor to the Fat Underground. Radical Therapy developed in the early 1970s as an in-your-face rebuke to the mainstream mental health profession. Conventional psychotherapy places the burden of change on the “maladjusted” individual; radical therapists condemned this as a “blame-the-victim” approach. “Change society, not ourselves,” they urged. Practitioners of Radical Therapy (or Radical Psychiatry, as some called it) prided themselves on having no professional credentials. The “problem-solving groups” wherein they conducted therapy were also training grounds for social activism.

A major concept of Radical Therapy is that oppression goes unchallenged if it is “mystified.” That is, its true nature is concealed. The oppressors do not say to the victims, “We will torture you until you submit to our will.” Rather, they say (and often believe), “This treatment may seem painful or unfair, but it is for your own good.” An example would be the practice of “protecting” women from sexual harassment by denying them access to education or employment in predominantly male fields. The Fat Underground viewed medical weight-loss treatments as a form of mystified oppression.

The other major precursor to the Fat Underground was the Fat Pride movement. This had begun in 1969 with the founding of NAAFA, the National Association to Advance Fat Acceptance. (In those days it was called, more ambiguously, the National Association to Aid Fat Americans.) Then, as now, NAAFA’s goal was full social equality and acceptance for fat people, within existing society.

Among the fat pride literature available in the early 1970s was the book Fat Power (Hawthorne Books, 1970) by Llewellyn Louderback. This groundbreaking work documented the rise of fat discrimination alongside the rise of the diet industry. Both of these, Louderback argued, relied more upon prejudice than upon medical truth or efficacy.

Prehistory

In 1972, a group of women from Los Angeles contacted the Berkeley, California, Radical Psychiatry Center, asking to be trained as radical therapists. Soon afterward, they formed a Radical Therapy collective and began problem-solving groups for women in Los Angeles. Among them were two founders of the Fat Underground, Judy Freespirit and myself.

The theory of fat then taught by Berkeley’s radical psychiatrists followed that of mainstream America, with a touch of rhetoric added for flavor: You’re fat because you eat too much, and you eat too much because you’re oppressed. Presumably, anyone truly living the life of a social revolutionary must be slim. By that criterion, Judy and I lagged somewhat behind the other radical therapists. No one criticized us for this openly. However, the issue was destined to arise.

It arose on the occasion of an invitation to our collective to speak about Radical Therapy at a local college. We worked in pairs. But when Judy and I both volunteered for this particular invitation, the collective balked. After a brief, embarrassed silence, one member summoned up the courage to say what was wrong: “You’re both overweight.” Unspoken, but understood by all, was that to be represented only by fat women would damage our group’s credibility.

To their credit, the collective moved beyond this fear and authorized us to go together to speak. We decided to use the audience’s anticipated negative reaction as the springboard for discussing how sexist standards of beauty oppress women.

Feminist theory aside, the experience with the collective was humiliating. I decided to try once again to lose weight. A trip to the Hollywood Public Library yielded the usual diet books, and also Fat Power. I found Louderback’s history of antifat attitudes interesting, but his medical and nutritional claims stunning. Ultimately, they would become the core of the Fat Underground’s medical arguments, so I will summarize them here.

First, fat people on the average eat no more than slim people on the average. Second, the long-term success rate of reducing diets, even the most “sensible,” doctor-supervised regimens, is extremely small: barely 1 or 2 percent. Third, fat people who live in nonjudgmental environments are free from at least one of the diseases (heart attack) most commonly associated with being fat.

Louderback’s book was written in a journalistic style, without footnotes. However, citations within the text enabled me to check out the sources, and indeed the sources backed up his statements. Nor were his sources obscure research papers. No, they were from public health documents summarizing years of published research, accessible to anyone with a library card. Most important, their findings resonated with the experience of one woman (myself) who had dieted almost continuously since the age of twelve, and was still fat.

Fat Power lacked a political analysis: Radical Therapy provided one. The belief that fat people are just thin people with bad eating habits now could be seen as part of a system of mystified oppression. With Judy’s encouragement, I presented this Idea to the Radical Therapy Collective. The response was mixed, but basically supportive. Judy and I contacted NAAFA and formed a chapter in Los Angeles. We recruited about six active members, both women and men.

From the start, our small NAAFA chapter took a confrontational stance with regard to the health professions. We accused them–doctors, psychologists, and public health officials–of concealing and distorting the facts about fat that were contained in their own professional research journals. In doing so, they betrayed us and played into the hands of the multibillion dollar weight-loss industry, which exploits fear of fat and contempt toward fat people as a means to make more money. We asserted that most fat people are fat because of biology, not eating behavior, and that the “cure”–dieting–actually causes diseases, ranging from heart attack to eating disorders. We rejected weight loss as a solution to fat people’s problems.

At first we relied upon the sources quoted in Fat Power to support our attack on the medical profession. About a year later, Lynn McAffee (Lynn Mabel-Lois), who had worked in a medical library, joined our group. She taught us how to gain access to medical libraries and to find information in the research journals themselves. Thus we became able to quote primary sources and advance scientific arguments in support of fat liberation. This won support for fat liberation among some mainstream health professionals.

In those days before the Internet, one important way to spread a message was to gain the support of existing groups that had access to the various media. Toward that end, we wrote position papers and lobbied leftist and academic health organizations to listen to us. Also, we contacted radio and television networks ourselves. Being in Los Angeles, we had access to the national television network offices and participated in several television specials about fat and weight loss in the United States. These experiences were always frustrating. The networks used doctors to present medical facts about the dangers of being fat. We “unrepentant fatties” were featured only for human interest. As soon as we attempted to present our own medical facts, filming would stop and the next guest would replace us on the recording stage.

Our confrontational stance eventually drew the attention of NAAFA’s main office. Although some of the leadership privately applauded us, officially we were told to tone down our delivery, and also to be more circumspect about our feminist Ideology, which most NAAFA members were not yet ready for.

In response, we quit NAAFA. The name of our new group, the Fat Underground, was suggested by Judy Freespirit; its initials expressed our sentiments. We numbered one man (who soon left) and four women. Judy and I wrote the Fat Liberation Manifesto late in 1973. In it, we expressed the Fat Underground’s alliance with the radical left and our intention to battle the diet industry. But as it turned out, we first had to battle a much more personal enemy: our “spoiled” feminine Identity.

What, Me Beautiful?

Early on a Sunday morning, one member, Ariana, phoned the others, saying, “We must meet, immediately! I have something to discuss.” She had been reading sociologist Erving Goffman on how people who are negatively stereotyped develop personality traits and behaviors that enable them to cope with their “spoiled Identities.” We quickly assembled in Ariana’s little stucco house. There she put forth her questions: Why do we not view one another as sexual beings? Why aren’t we sexually active? Why don’t we even talk about sex? It was true. In the sex-drenched environment of the 1970s, where sexy was a synonym for good (as in “That’s really sexy typing paper”), we still fulfilled the stereotype of the “sexless fat girl”: everyone’s best friend, no one’s lover.

So we started to talk. I don’t remember whether we touched on any profound truths that day. I do remember that we made some very good jokes. But bringing up the subject led to a thicket of related issues, which we managed to expose to sunlight throughout the next year.

Ariana had access to a cabin in a secluded mountain forest, about an hour’s drive from Los Angeles. There we went for occasional weekend retreats. We sunbathed in the clearing in front of the cabin. We talked or slept or read all day. We cooked the meals that we had fantasized about while on diets and ate double and triple portions, and then dessert, without shame.

The seclusion, the absence of men, and the abundance of simple physical comfort brought into focus our shared habit of seeing ourselves only “from the neck up.” We’d all been told that we had “a pretty face.” We decided that from then on, we were also beautiful from the neck down. But such a change required a new aesthetic. We learned about the ancient goddess images, such as the round little Venus of Willendorf, whose long, oval breasts draped over a perfectly spherical belly. We talked about learning to belly dance. We redefined flab in terms that could have come from the biblical “Song of Songs.” In Lynn’s words, “Your belly is like marble. Your arms are like the ocean.” We replaced the Amazon warriors of feminism with our own image of enormous, soft earth mothers.

A Broader Base of Support

By this time, Radical Therapy had become an important force in the local radical feminist community. The Radical Feminist Therapy Collective (RFTC) operated out of the Women’s Liberation Center. Judy and I were active in the RFTC, and Fat Liberation benefited by association.

Around us had grown up a small group of fat women who, although they did not feel bold enough to join the Fat Underground, recognized that Fat Liberation had something valuable to say to them, and they wanted to be connected with it. For them, the RFTC started the Fat Women’s Problem-Solving Group. The goals of this group were to help members stop dieting and build self-esteem.

In August 1974, the Los Angeles feminist community held a celebration of Women’s Equality Day, filling a local park with placards and booths. Thousands of women milled about, enjoying the sun, the crowds, and the atmosphere of sisterhood. The Fat Underground had a booth there, among the scores of others.

Several weeks earlier, the rock singer Cass Elliot, of the Mamas and Papas, had died. She was only thirty-three years old. Cass had become a star–an icon, even–to our generation, despite being very fat. Predictably, the press vilified her memory: a widely circulated report was that she had choked to death on a ham sandwich. In fact, Cass had been dieting at the time of her death, and we felt sure that her death was due to complications of the dieting.

The Women’s Equality Day celebration included an open microphone and stage. When our turn came, members of the Fat Underground, members of the Fat Women’s Problem-Solving Group, and some of our friends moved onto the stage. We carried candles and wore black arm bands, in a symbolic funeral procession. Lynn spoke. She began by describing the inspiration Cass Elliot had represented to us, as a fat woman who had refused to hide her beauty. She ended by accusing the medical establishment of murdering Cass, and (because they promote weight loss despite its known dangers) of committing genocide against fat women.

For the next few weeks, we were local heroines. The Los Angeles feminist news paper Sister devoted a full page in its next issue to Fat Liberation, with a photo of our Women’s Equality Day demonstration on the cover. Publicly, at least, local radical feminists began to acknowledge fat women’s oppression as a problem they would have to take seriously.

Membership in the Fat Underground increased briefly as new members joined; then, just as quickly, new and old members dropped out. Ideology, personality, priorities, and cold feet all played a role in the exodus. One founding member who left explained, “It will take too long to change society’s Ideas about fat, and I want to put my efforts where I’ll see success in my lifetime.” She joined other feminist groups and continues to promote Fat Liberation from within these. In the fall of 1974, the Fat Underground once again numbered only four members: Lynn, Gudrun Fonfa, Reanne Fagan, and myself.

We continued to give workshops and to study medical literature. We built coalitions with other feminist groups to plan citywide activities and to make sure that fat women’s concerns would be acknowledged in them. The Radical Feminist Therapy Collective formed a second fat women’s Radical Therapy group.

Around 1975, we began a new type of activity: harassing local weight-loss institutions. In a typical action, we would attend a “free introductory lecture,” pretending to be shopping for a diet cure. But when the lecturer would ask for questions, we would attack the program’s medical theory and success rate. Our goal was to shake the lecturer’s confidence and turn away customers.

Once, we disrupted a large behavior modification seminar at a prestigious university. For this occasion, we enlisted the help of all of our fat friends. As usual, a few of us sat in the audience, ready to ask questions that would attack the validity of behavior modification theory for weight loss. This was plan B, in case the main event failed. But plan A went off perfectly. Right in the middle of the program, Lynn led twenty supersize women onto the stage. She pulled the microphone from the hands of the astonished speaker and gave a one-minute speech of her own. Then, as quickly as they had appeared, the women left. From the audience, I saw what happened next. The moderator, her voice shaking at first, broke the stunned silence with a joke: “Look how much exercise they got! They walked all the way down the auditorium, and all the way up the stage steps, and all the way back!” A high point of these years: In 1975, Lynn Mabel-Lois was a featured speaker at a citywide women’s rally protesting crimes against women. She denounced weight-loss surgery as mystified oppression. Procedures such as intestinal bypass and jaw-wiring are considered healing rather than barbaric and dangerous mutilations, Lynn argued, only because fat is seen as a women’s problem.

A low point of these years: In 1976, dozens of fat women and friends picketed a major television network, because, in our opinion, it misrepresented the Fat Underground in a news feature on weight loss. However, this historical “first” went virtually unnoticed. Despite heavy prepicket publicity to both mainstream and alternative media, only one reporter covered the event. She was there because she was a friend of ours.

The “New” Fat Underground

In the summer of 1976, a major policy disagreement split the RFTC apart. The issue involved was not directly related to Fat Liberation. However, because the RFTC and the Fat Underground were so intertwined, the split hit the Fat Underground hard. All of the core members except Reanne soon moved out of state. As I am one of the ones who left, I now rely upon the recollections of Sheri Fram, who was new to the Fat Underground at the time, to complete the story.

By 1976, the Fat Underground had become recognized locally as a legitimate voice in Women’s Liberation. Feminist groups now invited them to speak. An especially fruitful relationship with the Women’s Studies Program at California State University at Long Beach led to the Fat Underground’s being invited to testify before the California State Board of Medical Quality Assurance on the abuses involved in prescribing amphetamines for weight loss. The confrontational style of previous years was dropped. However, the sense of urgency continued as before. In Sheri’s words, “Each event, each possibility of being heard, felt like an opportunity we could not afford to miss.” Throughout the next few years, members came and went. Sheri and Reanne remained the group’s anchors, speaking wherever they could. Meanwhile, news of Fat Women’s Liberation groups forming in other cities brought encouragement and support. A network developed that eventually became today’s size-acceptance movement.

In June 1982, Reanne was diagnosed with breast cancer. A year later, another tumor was found. She died in November 1983. The Fat Underground died with her.

While preparing this article, I asked several of the surviving members of the Fat Underground, “What did we accomplish?” Here are excerpts from their answers:

Judy Freespirit: “In the beginning, people giggled when we talked about Fat Liberation. Now . . . there are hundreds of thousands of fat activists and allies all over the world.”

Ariana: “We learned to reshape our minds and lives, not our bodies, in the face of tremendous pressure to do just the opposite.”

Sheri Fram: “We created a crack in the monolithic diet and weight-loss industry, and started a slowly growing revolution.”

Gudrun Fonfa: “By refuting the dogma of the diet industry and rejecting the aesthetics of the patriarchal culture, [we made] activists out of each individual fat woman who liberated herself from a lifetime of humiliation.”

Lynn Mabel-Lois: “We were audacious enough to understand what a failure rate means, and to criticize the medical profession. We expressed our rage and fought back.” ©

SARA GOLDA BRACHA FISHMAN was a founder of the Fat Underground in the early 1970s and distributed Fat Liberator publications later in that decade. She has gone by several names, including Aldebaran and Vivian F. Mayer. Sara now teaches and writes about science and Jewish spirituality in Worcester, Massachusetts.